|

|

|

Peter Cooper: American Manufacturer, Inventor and Philanthropist

by Jamir Phillips, NJIT

(1791-1883)

"My hope is that the love and desire for scientific knowledge will cause unborn thousands to throng the hall of Cooper Union to learn the beauties and to obtain the benefits provided in nature for the use and elevation of mankind. These will be known and enjoyed where men keep, subdue and hold dominion over the world and all that is in it. I trust the young will here catch the inspiration of truth in all its native power and beauty and find in it a source of inexpressible pleasure to spread its transformed influence throughout the world." - Peter Cooper, 1882

Peter Cooper was born in New York City to Dutch parents on February 12,

1791. Cooper did not attend a great deal of school throughout his youth.

Instead, his time was spent working with his father in various industrial

settings. During Cooper’s youth, trades were considered more useful

than education. The trades Cooper became adept in included: hat-making,

brewing and brick making, etc. His knowledge of machinery and manufacturing

increased throughout the years.

At the age of 17, Cooper became an apprentice to a Coach Maker in New

York City. For three years, he was employed in Hempstead, Long Island

were he made machines for shearing cloth. Cooper voyaged into entrepreneurship

by setting up his own shop providing the same service. This was an important

transitional period in Cooper’s Life. During the Second War of Independence

1812, business proved to be a success for Cooper but his profits soon

declined once the war was over. To stay competitive, Cooper converted

his facility to a furniture factory. Eventually Cooper sold the business

and took an interest in a grocery business, which was ironic for the fact

that it was opposite the future Cooper Union.

Cooper took full advantage of the shortcomings of American society before and during the Industrial Era. He saw that there were not enough skilled workers to supply the manufacturing needs of society. Cooper supplemented this demand for manufactured goods with the power of the machine. American soil was plentiful with many natural resources, which included wood, water, metals, etc. Land was plentiful, so expansion was not an issue. These resources provided the necessary conditions for success and growth for most manufacturing organizations within that era.

Iron has long been regarded as a key element in industrial development and compared to wood or copper, it is extremely strong. By heating it, iron is relatively easy to bend and shape using simple tools. Cooper had always fancied the idea of having his own Iron manufacturing company and this was just another business opportunity for him. Cooper had several Iron business ventures which included: manufacture of charcoal iron near Baltimore, a rolling mill in New York City, and several mines in Jersey and the Andover mine. Realizing the importance of this industry, Cooper purchased Ringwood Manor in 1853 for $100,000. The prospects for this purchase far outweighed Cooper’s previous ventures and with this new acquisition, his inventive spirit continued.

Some of the many inventions & successes of Cooper:

- Invented a machine for shaping wheel hubs.

- Concocted a method of siphoning power from ocean tides.

- Invented a rotary steam engine.

- Unveiled America’s first steam locomotive, known as the Tom Thumb (1825).

- Patented a musical cradle.

- Concocted a method for making salt.

- Obtained the very first American patent for the manufacture of gelatin (1845).

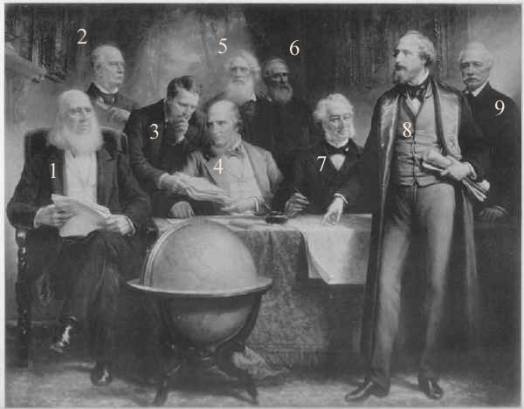

Another one of Cooper’s accomplishments involved in laying the first Atlantic cable. Cooper was also president of the New York, Newfoundland & London Telegraph Company and the North American Telegraph Company. Along with a few a of Cooper’s colleagues, the project for laying the Atlantic cable was completed. This project involved laying communication cable from Valentia, Ireland to Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, requiring the use of two ships because of the bulk of the 2000 miles of cable. The project was completed in 1858 and telegraph messages were exchanged between North America and Britain over a period of three weeks before technical problems caused the failure of the cable."

The following is an excerpt from Cooper’s diary (taken from www.atlantic-cable.com with the following illustration as well):

"After the two ocean cables had been laid successfully, it was found necessary to have a second cable across the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Our delays had been so trying and unfortunate in the past, that none of the stockholders, with the exception of Mr. Field, Mr. Taylor, Mr. Roberts, and myself, would take any interest in the matter. We had to get the money by offering bonds, which we had power to do by charter; and these were offered at fifty cents on the dollar. Mr. Field, Mr. Roberts, Mr. Taylor, and myself were compelled to take up the principal part of the stock at that rate, in order to get the necessary funds. We had to do the business through the Bank of Newfoundland, and the bank would not trust the company, but drew personally on me. I told them to draw on the company, but they continued to draw on me, and I had to pay the drafts or let them go back protested. I was often out ten or twenty thousand dollars in advance, in that way to keep the thing going. After the cable became a success, the stock rose to ninety dollars per share, at which figure we sold out to an English company. That proved to be the means of saving us from loss. The work was finished at last, and I never have regretted it, although it was a terrible time to go through."

| 1.Peter Cooper (President) | 4. Marshall O. Roberts | 7. Moses Taylor (Treasurer) |

| 2. David D. Field | 5. Samuel F.B. Morse (Vice President) | 8. Cyrus W. Field |

| 3. Chandler White (Secretary) | 6. Daniel Huntington | 9. Wilson G. Hunt |

During December 1858, Cooper was in the process of developing a conveyer system for ore mining. This conveyor system stretched three miles from Ringwood Mine to a forge at Boardville. The system was composed of seemingly endless amounts of ore that passed through large drums. The ore was carried by barrels that were suspended from the peak of the system. The barrels were capable of supporting a hefty 160 pounds. This system would prove to be much more efficient than conventional methods of transporting ore. There is not much information that states whether or not the conveyor system was completed.

To a large extent, Cooper’s success can be attributed to the early training which awakened his innate mechanical ability that made him revered as a pioneer even today. Cooper was not only concerned with his own success, he also believed that others less fortunate should have the opportunity to educate themselves and be successful as well. Cooper provided this opportunity to others by starting Cooper Union.

Cooper was responsible for most, if not all, of the Cooper Union’s design. Construction for the institution began in 1853. Steel I beams were normally used for the development of buildings of this size, but at the present time these beams were not available. Once again, Cooper’s inventiveness aided the project. He decided to use railroad tracks which were bolted together as a replacement for the steel I beams. The elevator shaft for Cooper Union was circular because Cooper felt it was the most efficient design. To Cooper’s surprise elevators were designed using a square template, but and inventor by the name of Elisha Graves Otis designed a special elevator for the school. Cooper poured over nine hundred thousand dollars into Cooper Union.

Cooper’s unselfish devotion and everlasting spirit lives on through his work. Cooper’s many ventures in life as an apprentice; mechanic, inventor, and humanitarian continue to affect many of our lives till this day. Cooper gave the less fortunate an opportunity to afford education, he was a great pioneer of The Industrial Era manufacturing steel and was even responsible for laying communication cable across the ocean. With all these accomplishments, Cooper’s saga lives on. Below is an article that was posted in “The Jersey City Express“edited by Otis M. Macmillan, after Cooper passed in New York city on the 4th of April 1883.

The death of Peter Cooper had plunged me into a peculiar strain of thought. Here was a man whose grand purpose in life was the elevation of the working classes, and to the realization of this object he devoted his time and money with what results is known to the world. On the other hand there is Wm. H. Vanderbilt, a man who devotes his hours by day and many of his hours by night to the accumulation of wealth. As I reviewed the characters of these men the contras they presented impressed me most forcibly. It would be hard in the whole category of human experience to find men differing in all important essentials more widely. One was a philanthropist, the other is a miser. One was benefactor, the other a stumbling block. One did well; the other is constantly doing harm. One helped his fellow-man - the other is injuring him. The death of Peter Cooper causes sorrow, even tears. The death of Vanderbilt would hardly cause a sigh of regret. And yet, of the two, Vanderbilt was and is the most powerful. His wealth, no matter how gained, is potent, and entrenched behind his bags of gold, his coupons and securities, he is enabled to defy and even to laugh at the will of the people. One was revered, the other is despised. One was loved, the other hated. One gave his wealth to the erection of a building that will prove a lasting monument to his love: the other spends his money on pictures for the artistic merit of which he has no perception, and gives balls for the amusement of his children and friends, the cost of which would keep many people from starvation. As I thought of all these things, I not only marveled at the inequality of human justice but was amazed at the peculiarity of the fate, destiny, or whatever you may it that dispenses favors so indiscriminately, and at the same time I thought here is a lesson by which the workingman will do well to profit. It teaches him that wealth is selfish and in the hands of some men a positive danger. Vanderbilt is the embodiment of the elements of monopoly. He uses his vast possessions for the oppression of the very men whose labor placed it in his coffers. In his person they have an admirable illustration of the effects of the monopolistic evil, an evil against which they should be strongly arrayed. Monopoly means the sacrifice of the rights of the many for the privileges of the few, the enrichment of the few at the sacrifice of the many. It is the modern case of Juggernaut under the ponderous wheels of which are dashed the honest product of labor. The death of Peter Cooper has instituted this comparison and I trust the lesson it so eloquently conveys will not be lost upon the men who toil.

Biographical Summary by the Friends of Ringwood Manor

Peter Cooper, inventor, industrialist, and idealist, was born in New York City and raised in Peekskill, New York. Not given the opportunity for a formal education, Cooper developed a mechanical inclination at an early age, which led to his pioneering, inventive, and philanthropic spirit.

At the age of seventeen, Cooper left his country home to become an apprentice to a prominent coach builder in New York City. In the years that followed, he owned and operated a furniture factory, a grocery, and a glue-making factory. The foundation of Cooper's wealth came through the development of a glue-making process which he patented in 1830. During this period he married Sarah Bedell (1813). Their marriage produced six children, of which only Edward Cooper and Sarah Amelia survived.

Cooper's other contribution to the industrialization of America included the first American-built stream locomotive (called the Tom Thumb), isinglass, gelatin (jello), and a new method of salt-making. He was also a founding member of the company that laid the first Trans-Atlantic telegraph cable.

Peter Cooper's greatest achievement was the establishment of the Cooper Union School for the Advancement of the Arts and Sciences in 1854. Cooper Union provided a free education to the gifted working class of New York City. He wanted to "give to the world an equivalent in some form of useful labor for all that I consumed in it."

One hundred and fifty years later, Peter Cooper's legacy of Cooper Union still provides scholarship for those students that excel in the arts, engineering, and architecture.

Peter Cooper died at the age of 92 from pneumonia at his home in New York City. An editorial from The Nation stated that Peter Cooper "was a man that united the highest integrity with the highest success."

For more information on Peter Cooper, see:

- The Making of a Modern Museum, by Eleanor Garnier Hewitt

- More Links

Peter Cooper | Abram Hewitt | Sarah Amelia Cooper Hewitt

Amy Hewitt (Green) | Peter Cooper Hewitt | Sarah Cooper Hewitt

Edward Ringwood Hewitt |Eleanor Garnier Hewitt | Erskine Hewitt

History | Architecture | People | Iron Industry | Tours | Contacts | Home

Directions to Ringwood Manor